Child Labor

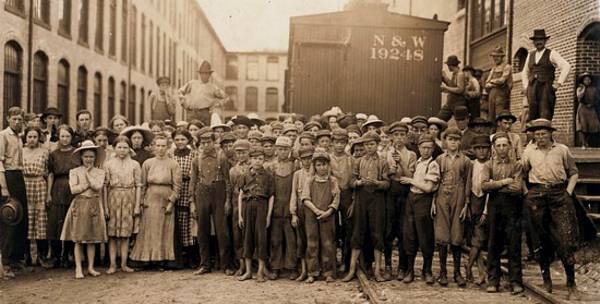

The workforce in a typical Southern cotton mill village looked like this:

Fig. 16. Photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, May 1911. Caption from source: A part of the spinning force working in the Washington Cotton Mills, Fries, Va. Group posed by the overseer. All work. The overseer said, "These boys are a bad lot." All were aware of the need for being 14 years old when questioned. Location: Fries, Virginia. Click here for full image.

The image above is not from the Avalon mill. It is from the Washington Cotton Mills, May 1911, located in Fries, Virginia. The mill was Colonel Francis Henry Fries' third mill which went into operation around 1902.

Child labor was commonplace in Southern cotton mills. It was not uncommon to find children under the age of twelve operating machinery.

There were quite a few children working in the Avalon Mill.1 Evidence of this is recorded in the 1910 census. According to the census, a quarter of the workforce in the Avalon mill was under the age of sixteen. The youngest workers recorded in the census were eleven years old. In 1910, The Department of Labor reported that there were two hundred and twenty-five people working in the Avalon mill.4

It is impossible to determine the number of children who worked in Southern cotton mills. When strangers came into the mills, the younger children were instructed to lie about their age. Parents wanting to keep their young ones employed, also lied about the ages of their children. At the time, the only way to determine a child's age was to either ask the child, the parent, or make a visual guesstimate. The state of North Carolina did not start keeping birth records until 1913.

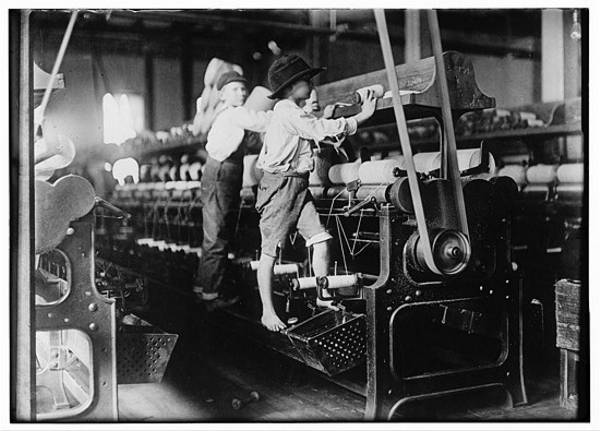

In the mills, the older children performed the same jobs as adults while the younger ones were used in jobs that didn't require tremendous skill or dexterity. However, there were hazards involved in working around the machinery. All ages worked twelve or more hours per day.1

Fig. 17. Photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, Jan. 19, 1909. Caption from source: Many youngsters here. Some boys were so small they had to climb up on the spinning frame to mend the broken threads and put back the empty bobbins. Location: Macon, Georgia. Click here for full image.

Owners of Southern cotton mills were not opposed pushing ethical boundaries in favor of profits. Not only from the perspective of child labor, but also the working and living conditions, in general. The child labor issue was more complicated than it may seem on the surface. We can not place all of the blame on greedy industrialists. While there were many who opposed child labor, others embraced it as an additional source of income. The wages earned by children were paid to the parents. In 1900 the state of North Carolina had minimal labor laws to protect employees and no laws to prevent children from working in the mills. One argument, for employing children, was the fact that children living on farms were put to work in the fields, alongside their parents at an early age. The justification was a simple comparison. If it was okay for children to work on the farms, why was it not okay for children to work in the mills? A popular argument given by mill owners was that children were better off working in the mills than on the farms. In 1906, Gertrude Beeks, secretary of the Welfare department of the National Civic Federation, backed this claim after visiting some Southern cotton mills: "Until compulsory education, with adequate school facilities is secured, the argument that the children are better off in the mills where they gain self-reliance and an industrial training cannot be refuted."7

To illustrate parents' ideas and concerns about the working situation, below are two letters2 from residents of either, Mayodan or Avalon. Avalon was served by the Mayodan post office making it difficult to ascertain with certainty who lived in which village. In this case, it doesn't matter, the working situations at both mills were the same. The letters, written in 1900, were in response to a questionnaire sent out by the North Carolina Department of Labor.

Suggestions for Mill Help

Mayodan, August 9, 1900

B.R. Lacy, Esq., Labor Commissioner, Raleigh, N. C.

Dear Sir:--I have given answers to the above questions concerning my individual trade. I also represent the cotton mill with my children and will offer some suggestions concerning their welfare. First, the wages paid per day, the highest gets thirty-five cents, lowest twenty cents (these are my children), Wages paid generally are from twenty cents to $1.50; second, mill hands works by the hour paid semi-monthly, cash in full; third, number of hours constituting a day's work are twelve--think it should be ten and fixed by law. Apprentice should enter the mill trade at twelve years, on half-time work to fifteen, then enter full time.

Yours sincerely,

Will Benton

Note: A Will Benton worked in the machine shop of the Avalon Mill.3

Needs of Cotton Mill Help

Mayodan, August 9, 1900

B.R. Lacy, Esq., Labor Commissioner, Raleigh, N. C.

Dear Sir:--Personally, I am not in the mill, but I represent it with my children and have given the above answers to the very best of my ability. I have seen several parties that labor in the mill, and they agree with me in the answers I have given; have also seen several parties that have received copies of the same, and say that they will not have time to fill out, but favor answers herein given. In regard to questions I think most important, will offer some suggestions to the encouragement of our Legislators to act upon at its earliest convenience. First, I don't favor the docking of hands for being too late getting in to work on the twelve-hour system, for more than a quarter of a day lost, or for the full time lost; second, the number of work hours during a week in our mill is sixty-nine, twelve hours a day for five days in the week, and nine on Saturday, counting recess for dinner time going to and from the mill, is about thirteen hours out, so we want a ten-hour system. Dr. Franklin said eight hours for work, eight for rest and eight for study, but we would be satisfied with a ten-hour system; third, at what age should children commence work? If we had a ten-hour system, they might be able to enter, males at twelve, females fourteen, but the answer given to the question on blank could be very well arranged and would be better if young hands could be divided so that one-half could work up to noon, the other half take their places in the afternoon; with that arrangement, they could have some benefit of schools from twelve to fifteen years of age; fourth, how many years should apprentices serve? I believe the time should be fixed by law, but am not able to say, as some are more apt than others. It generally takes about two years for a boy fifteen years old to learn to run mule spinning; other work in a cotton mill does not take near so long.

Yours truly,

H. W. Baughn,

The year 1904 saw the first child labor laws go into effect in North Carolina. The law limited the work week for all workers to a maximum of sixty-six hours and stated that no child under the age of twelve could be employed by a mill. However, the law came bundled with a list of mill-friendly exceptions which rendered the law a mere half-hearted intention. Stipulations were attached to the bill exempting engineers, firemen, machinists, superintendents, overseers, section and yard hands, office men, watchmen, and repairers of breakdowns.5 The law, which carried no provision for enforcement, empowered employers with a multitude of ways to ignore it.

In 1907, the child labor law was revised. The old stipulations were stripped and the law was reworded to state that no child under the age of fourteen shall be employed by or work in a mill. However, the law carried a new stipulation, boys and girls between the ages of twelve and thirteen could work in a mill under a apprenticeship providing the child had attended school for at least four months out of the preceding twelve.6 For the mill's management, a simple written note from the child's parents was all that was required for proof of age or schooling. The penalty for parents who lied about their child's age, or for mills found operating outside the realms of the law was set as a misdemeanor. The law also declared that no boy or girl under age fourteen were permitted to work in a mill between the hours of eight pm. and five am.6

- 1. Foushee, Ola Maie, Avalon: A North Carolina Town of Joy and Tragedy (Chapel Hill, NC: Books, 1977), 24.

- 2. Fourteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Labor and Printing of the State of North Carolina, (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton, 1901), 114-15.

- 3. Foushee, Ola Maie, Avalon: A North Carolina Town of Joy and Tragedy (Chapel Hill, NC: Books, 1977), 13.

- 4. Twenty-Fourth Annual Report of The Department of Labor and Printing of the State of North Carolina, (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton, 1910), 210.

- 5. Report on Condition of Women and Child Wage-Earners in the United States: The Beginnings of Child Labor Legislation in Certain States; A comparative Study, vol. VII (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1910), 212.

- 6. Uniform Child Labor Laws: Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Conference of the National Child Labor Committee, (Philadelphia: n.p., 1911), 176-77.

- 7. McKelway, A. J. "Welfare work and Child Labor in Southern Cotton Mills," Charities and the Commons: A Weekly Journal of Philanthropy and Social Advance (New York) November 10, 1906.

- Fig 16 - Hine, Lewis Wickes (1911), Location, The Washington Cotton Mills, Fries, VA., Photograph [from Library of Congress Digital Collections, accessed July 8, 2011, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ncl2004002762/PP//].

- Fig 17 - Hine, Lewis Wickes (1909), Location, Macon, Georgia, Photograph [from Library of Congress Digital Collections, accessed July 8, 2011, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/nclc/item/ncl2004001388/PP/].