Working in the Mill

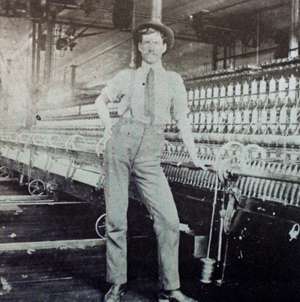

Fig. 15. The Avalon Mills, mule spinning. Emmett R. Suttenfield, overseer.

Workers were required to be on the job by six am.1 The work week consisted of sixty-nine hours: twelve hours a day, Monday through Friday with nine hours on Saturday. Sunday was the only day off. When deadlines had to be met it wasn't uncommon for work to go into overtime. Although some mills did, sources suggest the Avalon Mill never ran a night shift.

Mill villages were working villages. Long hours rewarded by low wages was the theme of Southern cotton mills. In 1900 workers in North Carolina cotton mills were paid: $1 to $2.50 per day for skilled men, 60 cents to $1 for unskilled men, 75 cents to $1.50 for skilled women, 30 to 75 cents for unskilled women, and 20 to 30 cents for children.2

With long hours and low pay, what was it that lured workers into the mill village? One of the attractions was a steady source of income.

Farmers and farm laborers found refuge in the mills. For many farmers, it was a move in a positive direction. The hours in cotton mills were long, but farm work often demanded an equal or greater number of hours. During the time, farm labor was more intensive as farmers weren't using tractors to tend the land. In farming, there were no guarantees of a successful crop. Bad years for crops devastated farmers while good years drove prices down. After years of toiling under the hot sun, the idea of earning a steady income and working indoors must have been welcoming for many farm laborers.

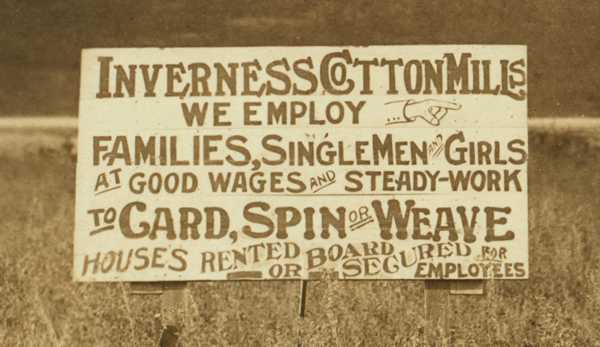

For others, the mill's available housing was a perk. People who migrated from other areas who had nothing or were uneducated could become gainfully employed and provide housing for their families at the same time. However, the company-owned housing was not a free benefit. Employees living in the village were obligated to pay rent. In mill villages, it was normal for rent to be charged by the room rather than by the house. It may seem as if this per-room renting arrangement was devised to keep large families out of the village — it wasn't. The mill required a certain number of employees to run the operation. The company built only the number of houses it deemed necessary to employ the mill. In order for this housing situation to work out, the company needed to have a certain number of employees per household. Through the eyes of the company it made more sense to employ entire families as opposed to individuals. Companies also understood that families with children to support were more likely to be loyal than an individual who wandered into the village with nothing. The cotton mills did hire individuals as well; however, these individuals usually boarded with other families in the village to maximize the number of employees per household. To encourage potential employees to live in the village, the cost of rent was kept lower than what was being charged elsewhere.3 Not everyone who worked at Avalon lived in the village. At least a few of the workers commuted across the river from the area known as Bentontown on Cedar Point Mountain.

Fig. 15.5 Photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, October 1912. Advertisement off the side of the railway near Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Sign reads: Inverness Cotton Mills: We Employ Families, SingleMen, and Girls at Good Wages and Steady-Work to Card, Spin, or Weave. Houses Rented or Board Secured for Employees

Many of those who ventured into mill villages for the perks found the situation to be a curse in disguise. Think about it: The company owned the employees' homes, the land they lived on, and controlled their incomes. When dry goods or food were needed the villagers purchased whatever was offered in the company store, spending the wages they earned from the same company. Because the mill was in walking distance of home, employees were accessible at all times and management was able to keep their workers under a watchful eye. The village being company-owned had no independent governing body or police-force to keep things in check. And to make things more interesting, add a complete lack of labor laws to this situation. The unfortunate truth was: There was nothing to stop the company from using their leverage to control and manipulate — not only the employee — but his or her entire family as well.

- 1. Foushee, Ola Maie, Avalon: A North Carolina Town of Joy and Tragedy (Chapel Hill, NC: Books, 1977), 77.

- 2. Report of the Industrial Commission of the Relations and Conditions of Capital and Labor Employed in Manufacturers of General Business, vol. VII (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901), 51.

- 3. "Southern Mills: Rent," The Protectionist: A Monthly Magazine of Political Science and Industrial Progress (Boston) May 1912, 15.

- Fig 15 - Unknown, Emmett R. Suttenfield (1900-1911), Location, Avalon, NC, Image [from Avalon: A North Carolina Town of Joy and Tragedy (Chapel Hill, NC: Books, 1977), 21].

- Fig 15.5 - Hine, Lewis Wickes (1912), Location, Winston Salem, NC., Photograph [from Library of Congress Digital Collections, accessed January 28, 2015, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ncl2004003673/PP/].